3 Books That "Changed My Life"

Sorry about the clickbait title. I really do love these books.

Most of us probably have things that we stopped doing as we became older. Nine times out of ten, folks will tell us that it is baggage we should let go of for our own good.

Something that I do miss from my childhood is the endless excitement of just lying flat on the ground and poring over a book. Thankfully, my current routine does leave some time for light reading.

Here are three books, from times past to the more contemporary, that had a significant impact on my life.

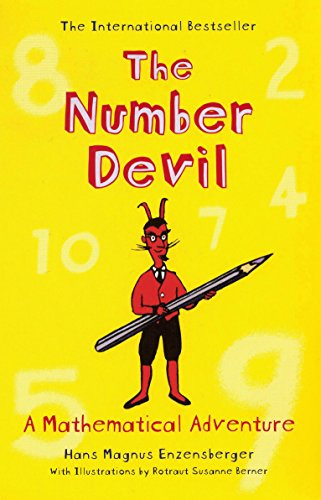

1. The Number Devil: A Mathematical Adventure, Hans Magnus Enzensberger

This is a special one, because it is a 1997 book exploring concepts in elementary to middle-school math that was originally published in German - and yet even when I read it as a high school student, the English translation of the book1 fascinated and enthralled me to no end.

In a devious blend of illustration and storytelling, the book weaves skillful science communication into ordinarily abstract concepts such as the Fibonacci sequence, and creates something that captures the imagination of both children and adults.

The premise? A young boy named Robert - the main character - meets a “devil” in a series of dreams, and together they explore mathematical abstractions. The reader follows Robert as his perception of math changes, eventually culminating in interest and a better relationship with numbers than he had before. It is ingeniously metafictional, as Robert’s journey precisely mirrors the intended journey of the reader.

Lots of credit is also due to Rotraut Suzanne Berner, whose whimsical illustrations were instrumental to the enjoyment of the narrative:

It is difficult to fully explain the magic of this book in these brief paragraphs, but suffice to say that on many occasions my younger self wished for the Number Devil to appear in my dreams. As I grew older, I still found much pleasure in revisiting these pages - and even as I write this now, I am tempted to check it out once more.

Importantly, even though I leaned more towards an arts and humanities education in my youth, books like The Number Devil were key in holding my interest and capturing my imagination in mathematics and the “hard sciences”, and played a big role in shaping my interdisciplinary ethos.

2. The Diving Bell and The Butterfly, Jean-Dominique Bauby

Sitting in my shared dorm at the Australian National University in 2014, I flipped opened an unreliable HP Envy laptop (they were really not the best in 2014), excited to watch the first lecture of the Understanding the Brain: The Neurobiology of Everyday Life MOOC on Coursera. Those were the early (and arguably the best) days of Coursera - where many instructors of the courses were heavily engaged and participated in discussions with current students despite the asynchronicity. Back then, not as much content was gated off by paywalls as well.

It was a cold day in Canberra, and I had just returned from hiking the Black Mountain Summit Trail with my friend Alicia Ng, with whom I was on exchange (a semester-long study abroad program offered by the National University of Singapore with partner universities around the world). As Singaporeans, the comparatively laid-back Australian lifestyle felt at once liberating and jarring. We found ourselves with much more free time on our hands than expected. While I spent a bulk of it exploring the great wilderness of Down Under, and other times dishing out pentakills in the Oceanic League of Legends server, I also had time left over to indulge in the delightful world of MOOCs.

Peggy Mason, Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Chicago, leads the course. In her initial lectures, she introduces Bauby’s book, The Diving Bell and The Butterfly.

Dr. Mason’s impassioned pitch about the book’s relevance made me immediately go out and search for a copy at the school bookstore. And find one I did. The cover was nothing to write home about - on first glance I thought that it would be a book that leaned towards the formal, and that it would take some effort to get through. Never had there been a truer “don’t judge a book by its cover” moment. I was hooked from the moment I opened the cover to the first page.

Jean-Dominque Bauby, the author, was a French journalist and editor at the prominent fashion magazine Elle. He was also an unfortunate victim of Locked-in Syndrome (LIS)2, following a seizure at the age of 43. He communicated the entire contents of the book through only eye movements with the help of a speech therapist who used a system known as partner-assisted scanning3, and a ghostwriter who recited the alphabet and transcribed as Bauby blinked at the letters he wanted to write.

Written from the author’s perspective, the book is a whirlwind of Bauby’s incredible eloquence as he reflects on his life before LIS, during LIS, and his emotional journey through and into this condition. At least two chapters left me in silent tears - the most poignant segments were those where he speculated on experiences he had not yet tried before succumbing to LIS, and those where he spoke of simple pleasures taken for granted.

LIS, in my imagination, is both terrifying and tragic. It is terrifying to imagine being locked inside a body you cannot control; aware but unable to interact with and fully experience the outside world. It is tragic because you remain observant of your surroundings, but are unable to participate, to fully communicate, and to be understood. It is the most literal manifestation of “the world passing you by”. Yet Bauby, with both his experience as a writer and his deep self-awareness, narrates with uncanny warmth, sincerity, and poise about his ordeal, even as he laments his condition and lost opportunities.

Bauby’s words will strike a metaphorical chord with those who have experienced some form of loss or tragedy, or who are struggling with their mental health. The book is a sincere recommendation from me to everyone - whether you are doing great or not so great - because it comes from a very personal perspective of someone who has suffered the ultimate loss: the loss of one’s own agency in life. Wherever you are in your own journey, this read will provide much needed perspective towards making the best of it.

For a long time, I thought that the most difficult ordeal I would experience was my close encounter with death at nine years of age. It was an intestinal condition that struck me on October 1st, 2000 - Children’s Day in Singapore - and resulted in massive blood loss that would have claimed my life had my parents not sent me to the hospital in time. Being in a wheelchair, having needles, catheters, and feeding tubes inserted and removed on a regular basis, counting down on the operating table, not really knowing what was to come, and on top of that the months of pain and inconvenience that followed - I became acutely aware of what the lack of agency feels like. The experience would go on to shape my perspective (and fashion me into somewhat of a Stoic for the better part of my youth - a perspective that I eventually left behind), and yet, it proved to be not the hardest ordeal by far.

Four years ago, I was left heartbroken by a long-time partner who I believed was the love of my life. Without going into unceremonious detail, going through the hospital ordeal a hundred more times would not even come close to the pain and consequences of genuine heartbreak. In the some of my darkest moments - staring out the window of my apartment in Chicago, or being on my knees in the midwestern winter snow as I composed myself from an anxiety attack - the memory of Bauby’s words would come back, and lift me up in their own small way.

3. Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things that Matter, Peter Singer

Peter Singer has to be one of my favorite contemporary philosophers, and his consequentialist approach to applied practical ethics is something that I believe is sorely needed in our society today. I would definitely cite Singer’s ethical framework as a significant influence on my own consequentialist and sentientist worldview.

At the core of his philosophy is secular utilitarianism - a concept that often looks and sounds ideal to many, yet proponents of it often fall short in practical execution and analysis. Singer, through his relentless analysis of global issues and deconstruction of real-life moral dilemmas, is a cut above the rest in deriving actionable ethical guidelines from his brand of duty-based act utilitarianism.

I first picked up Ethics in the Real World in 2016 while browsing with my ex at a Kinokuniya in Singapore, thereafter spending a year to digest it - not because the book was in any way a difficult or heavy read (much to the contrary, Singer’s writing is exceptionally concise and engaging), but because every essay was inspired and provocative, and gave me significant pause to ruminate on the topics being discussed.

The book features short essays that appeared on various columns and publications throughout Singer’s active years, and discuss thorny issues from abortion rights and the morality of incestuous relationships, to the phenomenon of “tiger moms” and the ethical cost of high-priced art. Among some of my favorites are a treatise on why paying more for commercial flights if one weighs more is a morally sound policy, how we should give to charities with “our heads” as opposed to “our hearts”, and whether doping in competitive sports is ethical - spoiler: Singer believes that perhaps it should be a legal part of the meta.

Singer is also a prominent advocate for animal rights and abortion rights, and given some of the controversial topics described above, it is no surprise that he has faced significant pushback throughout his career. Traveling from his home country of Australia in 1999 to take up the post of Princeton University’s first professor in Bioethics, he was immediately greeted with protestors who blocked his access to Nassau Hall, where he was to give his inaugural lecture. The issue: Singer’s vocal support of euthanasia for some infants with disabilities. Singer continues to provoke dissenting voices to this day, and has faced recurring protests at Princeton University and the University of Victoria.

A friend at the National University of Singapore once told me this about his own interest in academia: that his ultimate goal was to “get everyone to hate him”. Humor and jest aside, the subtext of this statement was that a big part of innovation and creating new knowledge is challenging existing viewpoints - and doing so in a productive way is certain to draw ire from many folks, especially those deeply embedded in existing paradigms and ways of thinking.

I tend to agree, and am a proponent of this mindset in other aspects of life - if there are folks that dislike you, take it as a compliment because you must be doing something so useful and so impactful, that people are willing to expend energy just to resist or undermine your influence. And if that is any yardstick to go by, Peter Singer passes it with flying colors - all the more reason for one to go pick up his book, and savor it like it fine wine.

Translated by Michael Henry Heim.

Locked-in syndrome, or pseudocoma, is a condition where a subject is conscious and aware, but suffer from complete paralysis of all voluntary muscles except for the ones that control the movements of the eyes.

Partner-assisted scanning is a broad term for strategies used to communicate with a non-verbal and motor-impaired subject, via the presentation of stimuli in a sequential fashion and agreeing upon a “yes” response.